In this blog series, I discuss how I came to research, write and rewrite a book about genocide for young readers in just one year. This is the first post.

It was late in 2017 when Lyn White contacted me to ask if I was interested in writing a book about the Rohingya conflict for 11–14 year old readers. She explained that she was the Series Creator and Editor of Through My Eyes, a suite of 10 novels that examines the experiences of children living in war zones or natural disaster zones. Lyn had seen me speak about my writing on Burma (or Myanmar as the country is now called), the land where I was born. She felt I had the right background to write a book for the series.

Several weeks earlier, the UNHCR announced that 10,000

Rohingya refugees had arrived at the Bangladesh/Myanmar border in a single day.

Nearly 1 million Rohingya refugees had fled Rakhine state for refugee camps in

Bangladesh, chased out by armed forces. Myanmar’s powerful generals were accused

of ‘ethnic cleansing’.

I was appalled by the news. But write a book about it? That

was a different matter.

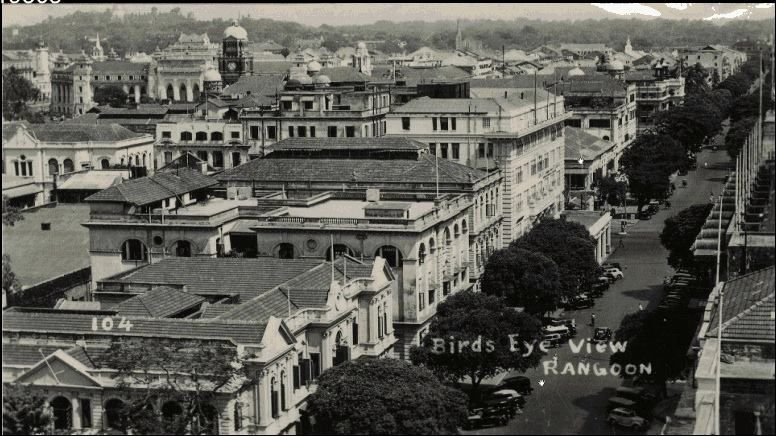

What Lyn didn’t know was that although I was born in Rangoon

the country’s former capital, I had left Burma as a small child. My first return visit to Burma was in 2013.

My parents warned me that this book could mean I would never

set foot in Burma again. Their fears were grounded in our family history. I

hadn’t returned to Burma until 2013 because I hadn’t been allowed to. No one in

my family had. Burmese expatriates had been denied visas by the junta for

decades. When we left in 1963, my maternal grandparents and great grandmother

had remained behind. We grandchildren only knew them through their letters on thin

blue aerogrammes. My mother never saw her father or grandmother again. One of

the first things I did when I returned in 2013 was visit their graves. And that

feeling of having two generations of my own people in the ground beneath my

feet was unlike anything I’d ever felt before.

As an academic, most of my research is about Myanmar and I travel there frequently. But my reservations were personal. Would it be worth writing this book if it meant never being allowed back in? Was I okay with saying goodbye to Burma, that maddening, beautiful, heartbreaking country — in emotional ways, still my country — all over again?[1]

There were other complications to writing this story. Since

the coup in 1962, Burma had gradually sealed herself off from the world. Travellers

weren’t allowed in for more than 10 days at a time. The country became secret,

silent and remote until in the 1980s when Burma began to be referred to as a

pariah state. This meant that our target readership would know next to nothing

about Burma/Myanmar. Saying yes to Lyn’s proposal, meant I would have to do a

lot of explaining – first about Burma

and secondly about the Rohingya situation. To get those explanations right

would require a heap of research.

If I said yes, I would have to deliver a first draft in just

months. While the average stay of a refugee in a camp is around 20 years, the

news cycle is far shorter. The book had to be ready to go while news outlets

were still reporting on the conflict. Novels, however, usually take years

not a year. Like most writers, I have a day job. I teach at RMIT

University in Melbourne, Australia. Would I really be able to finish a book this complex within

the deadline?

Yet how could I say no?

The persecution of the Rohingya was terrible. And from what I had seen

in my recent trips to Myanmar, the ordinary people of Myanmar were still

traumatised by decades of military rule which had ended only a few years

earlier. They too were vulnerable, although in a different way. The transition

from dictatorship to ersatz democracy was painful. There had been such hope for

the country after Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy won the 2015

general election in a landslide, defeating the military government. It had

seemed that Burma would continue the process of political liberalisation and,

after 50 long brutal years of military dictatorship, would at last become a

free democracy. The Rohingya crisis had shown that this freedom was still a

dream.

It was this realisation that final made me agree. As an insider,

I had some insight into Myanmar culture. As an outsider, I could be accurate

and impartial when I needed to be. So I finally signed the contract.

I had just five months to write forty thousand words.

Could I do it?

[1] I tested whether I would get a visa in June 2019.

Although the book was not yet printed, some of the promotional material up on

the Allen & Unwin website mentioned the military. At my request, Allen

& Unwin redrafted the promotional material, omitting mention of the

military, just in case it offended the authorities in Myanmar. I was allowed a visa and visited without

incident.